Introduction to fee bumping

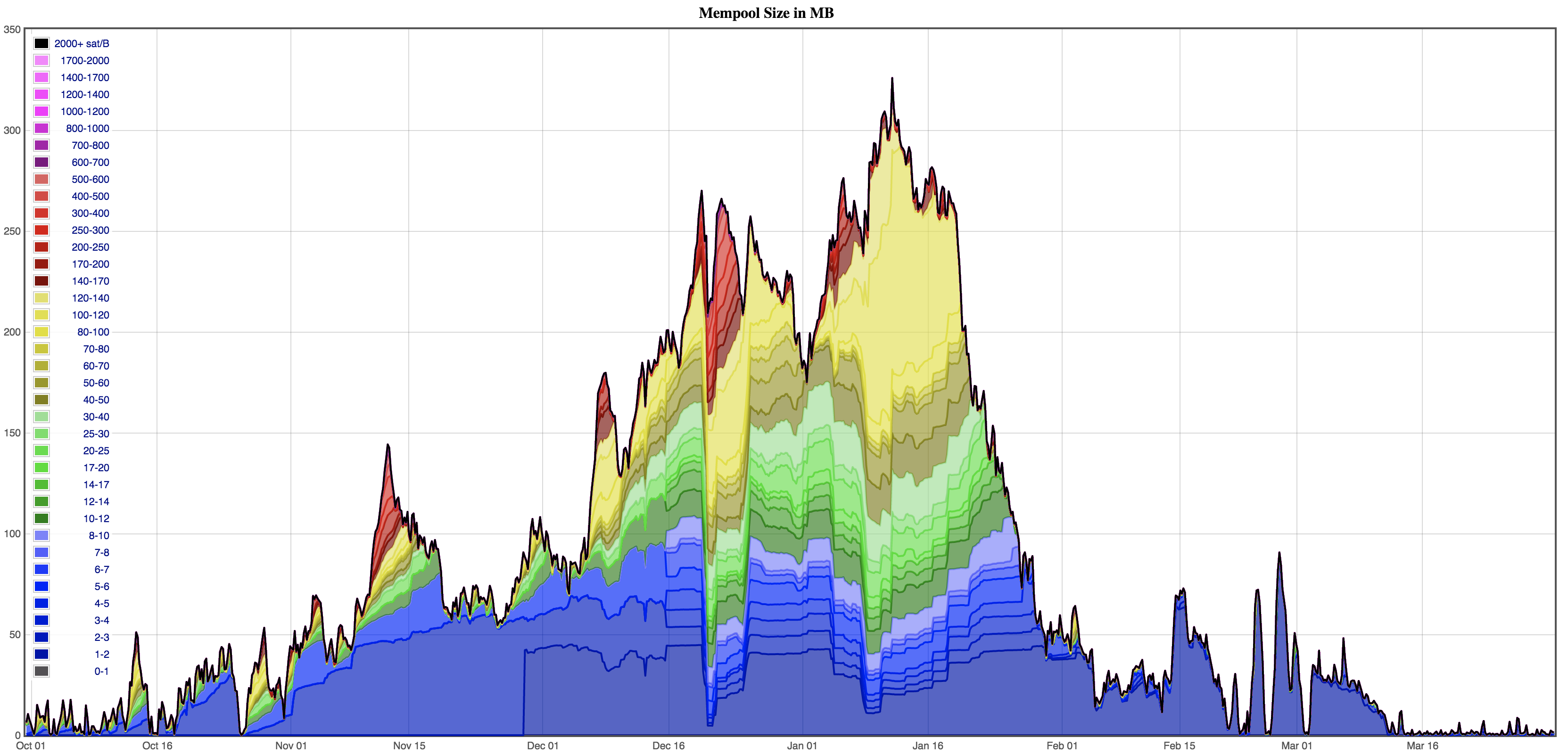

The fee market in Bitcoin can be very dynamic, with the fee-rate required for a transaction to be included in a block increasing or decreasing rapidly.

(Six months of mempool size, grouped by fee-rate, from https://jochen-hoenicke.de/queue/#1,24h)

One of the reasons for the volatility in the fee-rate is that the mechanism used to select what to include in a block is a market. In this market, the miners supply 4Mweight of block space every ~10 minutes and users bid (through transaction fees) to have their transaction included in a block. Different wallets’ fee estimation algorithms are often naive and users are sometimes insensitive to high fee-rates, which means that when the mempool grows to more than a few megabytes and expected confirmation times start rising, a rapidly escalating bidding war can ensue, with wallets attaching extremely high fees to transactions.

This market has one strange quirk: if a user’s bid is unsuccessful and the transaction isn’t included in a block, the bid is not withdrawn, and is still valid for the next block. This is because transactions have an invariant property that once they’re valid for inclusion in a block, then they will be valid for inclusion in any subsequent block. In fact, the only way to invalidate an already valid transaction (and thereby ‘withdraw’ that transaction’s bid for block inclusion) is to spend its inputs in a conflicting transaction.

This quirk generally isn’t a problem for users, since if a user signs a transaction and they’re happy for it to be confirmed now, then presumably they’d be happy for it to be confirmed at some point in the future for that same fee-rate. However, there is one scenario in which the inability to withdraw a transaction from the mempool can become a serious problem for users: when the user has not attached a high enough fee-rate for the transaction to be confirmed in a block, and the user has an urgent need for the transaction to be confirmed. This could happen for many reasons: the wallet or user has underestimated how much fee is required, the user has tried to save fees by bidding at the low end of the fee estimation range, or the required fee rate has just spiked unexpectedly after the transaction was broadcast. Whatever the reason, the user finds himself with a transaction that is ‘stranded’ in the mempool with a low fee rate, and a very low chance of being confirmed in future blocks.

The risk of having a transaction getting stuck impedes on users’ leeway to make low bids on transaction fees. If there is no way to get a transaction unstuck after it’s been broadcast, then users are forced to bid conservatively (high) to avoid the risk of having their transaction get stuck.

We therefore need a method to bump up the fee on an already broadcast transaction for a couple of reasons:

- To allow users to ‘unstick’ an already broadcast transaction.

- To give users the leeway to bid low on transaction fee-rate, with the option to later bump the fee up.

The solutions

There are two common solutions for unsticking a payment that is stranded in the mempool: Replace-by-fee (RBF) and Child Pays for Parent (CPFP):

Replace By Fee (RBF)

The user constructs and signs a replacement transaction which spends one or more of the same inputs as the stuck transaction but pays additional fee (usually by reducing the amount of bitcoin for the change output and leaving the extra value as additional fee). If the replacement transaction attaches enough fee, then miners will be incentivized to include it in a block.

Child Pays For Parent (CPFP)

The user creates a new transaction which spends one or more of the outputs of the stuck transaction. This child transaction attaches a large fee - enough to increase the combined fee-rate for itself and the stuck transaction above the required fee-rate for inclusion in a block. Note that this is only possible when the user owns some of the outputs

When selecting transactions for inclusion in a block, miners will consider ‘packages’ of transactions, and will look at the total fee-rate across the entire package of ancestors and descendants. The miner is incentivized to do this to maximize the total fee yield from the block.

This feature could rightly be called Descendants-Pay-For-Ancestors since a rational miner will try to maximize their fee by considering packages of transactions greater than 2 deep. For example, the Bitcoin Core mining code considers packages of up to 25 transactions in any length of chain.

User experience considerations

Fee bumping strategy has a very visible impact on user experience of a Bitcoin wallet or service. Bitcoin services need to consider issues such as:

- Having no fee bumping strategy at all can lead to very poor user experience in cases where mempool fee-rates spike and a transaction becomes stuck indefinitely.

- Some services offer Service Level Agreements that guarantee confirmations within a certain number of blocks or within a certain time period. Failing to meet those SLAs leads to customer complaints and tickets. (Whether such SLAs are realistic or desirable is outside the scope of this document!)

- Some Bitcoin wallets and services treat transactions that signal opt-in RBF differently from those that don’t (for example not showing RBF transactions in a user’s balance). This can be confusing for users sending from wallets that signal opt-in RBF.

- Fee bumping with RBF creates a new transaction with a new txid. This can be confusing for users if they don’t understand that a payment’s txid/vout index will change when the transaction is RBF’ed.

- Fee bumping with RBF invalidates the signatures in the original transaction and requires all signers to re-sign. This is especially problematic for multisig transactions or where signing is done on a dedicated hardware wallet or HSM.

- By definition, fee bumping increases the fee attached to a transaction. For CPFP especially, the new fee can be significantly higher. Accounting for that fee and who pays it (the user or the service provider) can be difficult.

These issues will be discussed in more detail in later sections of this document.

Considerations for high volume users

There are additional considerations for entities that make heavy use of the Bitcoin blockchain, such as exchanges or custodians:

- Services have a certain number of UTXOs in their hot wallet. If all of those UTXOs are tied up in stuck transactions, and the service’s wallet doesn’t use unconfirmed UTXOs as inputs, then they can run out of UTXOs for new transactions.

- Using opt-in RBF allows services to ‘low ball’ their initial fee-rate. If the transaction fails to confirm in the desired time, the fee can be bumped. For entities sending a lot of transactions, the savings in fee can be significant.

- Using CPFP to bump the fee can increase the total fee significantly, since the total fee has to pay for both the child and parent transactions - whereas an RBF transaction is replaced entirely and so doesn’t need to provide fee to cover an extra transaction. For entities sending a lot of transactions, the additional fees can be significant.

- Services that are very frequent spenders and broadcast transactions to the blockchain every block can chain together spends and use CPFP without any additional overhead. If a transaction has not been confirmed by the time they need to broadcast their next transaction, they can use the change output from the first transaction in the second, and attach enough fee to bump the feerate across the entire package.

- Services that use payment batching effectively can bump many payments with a single RBF or CPFP.

- Services that are not using payment batching can use a large CPFP to bump multiple transactions at the same time, and potentially consolidate the UTXOs from those multiple transactions at the same time.

- The mempool code only allows transaction packages of up to 25 unconfirmed transactions (with a maximum weight of 404Kweight), so there’s a limit to the number of transactions that can be bumped with a single CPFP transaction.

- Services that have a coin selection algorithm that is effective at change avoidance will have many transactions without change outputs, which can’t be bumped using CPFP. Larger wallets are able to avoid change more often since they have a larger set of UTXOs to choose from.

These issues will be discussed in more detail in later sections of this document.

Introduction to RBF

TODO1

Overview of what RBF is

TODO2

History of RBF

TODO3

BIP 125

TODO4

5 conditions for RBF

TODO5

User Experience Recommendations

Even wallets and services that do not themselves support creating opt-in RBF or replacement transactions should present a clear and accurate experience to their users when dealing with RBF transactions:

- wallets that receive transactions that have opt-in RBF signaled may display that the transaction is signaling opt-in RBF (with a tooltip or pop-up box giving additional information about RBF).

- wallets must not double account replaced transactions (ie count a debit or credit twice if it appears in a replaced and replacement transaction).

- wallets and block explorers should continue to show replaced transactions after they have been replaced (either grayed out or hidden), with a clear indiction that the transaction was replaced and is no longer valid.

- wallets and block explorers should include information about the previous transactions that a replacement transaction has replaced. For example, if transaction A2 replaces A1, the page for A2 should include the information that “this transaction replaced transaction A1”.

- Links to transactions that have been replaced should remain live on block explorers. They may redirect to the transaction which replaced them.

Interoperability & compatibility matrix

TODO6

Example of a company using RBF

TODO7

Child-Pays-For-Parent

Child Pays for Parent (CPFP) is a wallet feature where a user spends the output of an unconfirmed (parent) transaction as an input to a new (child) transaction. The wallet attaches enough fee to the child transaction to increase the combined feerate across the parent and child transactions.

How does CPFP work?

When constructing a new block, miners are incentivized to fill the 1vMB with the set of transactions that maximize the transaction fees. If all unconfirmed transactions were independent, this would be a very straightforward operation - the miner would select the transaction with the highest feerate and add it to the candidate block. She’d then take the transaction with the next highest feerate and add it to the block. She’d continue to do this until the block was full. This trivially maximizes her profit from the block (with a little complication around the final few bytes of the block to ensure that she’d maximally filled the block).

However, unconfirmed transactions aren’t independent. It is possible to have chains of unconfirmed transactions by spending the output from a transaction before it is included in a block. For example, if tx A has two outputs a1 and a2, transaction B could use one of those outputs as an input before A has been included in a block. In this case, if the miner wants to include transaction B in the block, she must also include transaction A, since without A, B is spending a non-existent output and is invalid.

If the miner considered transactions independently when constructing her block, she may forego transactions with very high fees if they depended on transactions with very low fees (or worse, she may construct an invalid block with a transaction that depends on an unincluded transaction). To maximize her profit, the miner should therefore consider transactions in packages (sets of transactions with dependencies on each other) when constructing a new block.

Wallets can take advantage of this rational behavior by miners to incentivize them to include a stuck, low-fee transaction, by spending one of its outputs and increasing the total feerate across the transaction package.

History of CPFP

For users to be able to bump a transaction using CPFP, two elements are required:

- a wallet that will spend the output of a stuck unconfirmed transaction in order to bump the combined feerate.

- The expectation that miners will maximize their profit by considering packages of transactions.

Before 2012 blocks were rarely full and so there was no fee market. The Bitcoin Core mining component was therefore not very optimized to maximize transaction fees when selecting transactions for block inclusion. Transactions were first ordered by ‘priority’ (the sum of the (value X coin age) for each transaction input, divided by the transaction size), with an increasing feerate required as the block filled up. Bitcoin Core PR #1590 changed the mining code to predominantly sort transactions by feerate, with some space reserved for transactions with a high priority score. Version 0.7.0, released in September 2012 was therefore the first Bitcoin Core release to primarily order transactions by feerate.

At around the same time, Luke-jr started maintaining a patch which took into account the transaction fee of children transaction when sorting transactions for inclusion in a block. This patch was used by at least some miners, but was never merged into Bitcoin Core due to a lack of testing and benchmarking, and concerns that it could open a DoS vector against miners.

The Bitcoin Core mining code was updated in 2016 to better account for packages of transactions. The mining code will consider packages of up to 25 transactions or 101vkB. This change was included in V0.13.

At the time or writing (November 2018), it is almost certain that a majority of miners are running Bitcoin Core V0.13 or later, or a derivative thereof. Wallets can therefore safely assume that descendant transaction fees will be taken into account when miners construct blocks.

CPFP case study

The Hodlers Bitcoin Exchange (HBE) has several hundred thousand customers and services thousands of withdrawals per day. Since they need to send many withdrawal payments in every block, they batch withdrawals into a single transaction every ten minutes.

HBE likes to keep fees low for their customers, so they set their transaction fee very economically - they prefer to pay just enough to get into a block, but no more! Occasionally, this means that the batch withdrawal transaction is not confirmed and gets stuck in the mempool. This leads to customers complaining about slow or stuck transactions.

To improve the experience for their customers, HBE implemented CPFP to bump the feerate on stuck batch withdrawal transactions. To do this, they use the change output from one batch withdrawal as the first input into the next withdrawal, and make sure to include enough fee on the second withdrawal to raise the average feerate across the two transactions. If that still doesn’t bring the feerate up to a high enough level to be mined, they then use the change output from the second batch withdrawal as the input to a third batch withdrawal, and so on.

There were a number of aspects that HBE needed to consider when implementing their CPFP system:

- they need to ensure that every batch withdrawal includes a change output that comes back to them. If there’s no change output, then they can’t construct a child transaction to bump the fee of the parent transaction.

- they needed to do careful testing around the fee rate logic. The child transaction must pay for the parent transaction, so their algorithm needed to take the weight of the parent transaction and the fee that had already been paid into consideration when calculating the average fee rate. They needed to do the same process when creating a 3rd or 4th generation transaction to pay for its ancestors.

- the Bitcoin Core mining algorithm will only consider packages of up to 25 transactions or 101vkB. HBE therefore needs to make sure they’re not creating chains of transactions larger than that.

Overall, HBE is very happy with their new CPFP implementation. Support tickets are down, and customers are usually unaware that their withdrawals are being fee bumped using CPFP, since the transaction id and output index of their withdrawal does not change.

User Experience Recommendations

Wallets and explorers should present relevant information about transaction packages to users:

- if an unconfirmed transaction is part of a package of unconfirmed transactions, the service should allow an expert user to view ancestor and descendant feerate of the transaction alongside its feerate, to allow the user to more accurately predict the package’s chance of inclusion in future blocks.

- block explorers may display transactions as ‘malleable’ if any of their inputs are non-segwit. Malleable transactions may not be safe to include in chains of unconfirmed transactions, since malleating the signature invalidates any descendant transactions.

RBF or CPFP (or both)

TODO8

Advantages of RBF

TODO9

Advantages of CPFP

TODO10

Using both together

TODO11

Implementation gotchas

TODO12

Conclusion

Both Replace-By-Fee and Child-Pays-For-Parent are useful techniques for bumping the fee on a stuck unconfirmed transaction. Each comes with its own benefits and drawbacks, and depending on the situation it may be appropriate to use one or the other (or both together).

Bitcoin engineers should be familiar with both techniques, and Bitcoin products and services should present a clear and accurate experience to users when those techniques are being used, even if they do not support creating RBF or CPFP transactions.

Footnotes

Consensus, policy and incentive compatibility

Both solutions discussed in this article are related to network node and miner behavior before a transaction is included in a block. That behavior is therefore a question of policy rather than consensus. Both solutions are also miner incentive-compatible - a miner who is trying to maximize his revenue will accept both RBF’ed transactions and CPFP packages. Individual nodes’ mempools (which should be a node’s best guess for what will be included in the next blocks) should therefore also accept RBF’ed transactions and CPFP packages.

Previous:

Introduction

Next:

Return to table of contents